Dickinson's Landing

Old aerial photo of the village of Dickinson’s Landing

circa late 1940s. On the left is Hoople’s Creek, almost centered is Upper Wales Rd., and Lower Wales rd. near the right side of the photo.

DICKINSON’S LANDING by Fran LaFlamme

The following essay was found among the papers obtained from the Fran Laflamme estate.

In 1957, Dickinson’s Landing was like any other village in Eastern Ontario. It was a long, narrow strip, lying on the bank of the St.Lawrence River, with a north side and south side, cut in two by her Majesty’s Highway #2. At the west end was Hoople Creek and the east boundary was marked by the Wales Road, where Summers Elliott’s Texaco Station marked the eastern entrance to Dickinson’s Landing, just as today, his Texaco station marks the entrance to Dickinson’s Drive here in Ingleside. It was a police village, with men looking after its interest; Eldred Markell, Ray Wells and John Murphy. It is not unfair to call it a sleepy village, because it could boast only one general store, one service station, one church, one school. And so, when 1957 brought an end to all our villages, Dickinson’s Landing petered out, and yet it had wrapped up in its few hundred short years, a considerable history.

In a way, this history paralleled the history of many little villages in Eastern Ontario. Legend has it that Dickinson’s Landing began as an outpost in the day of Sieur de Lasalle, who came from Lachine about 1669, along with two priests, set up a fur trading centre, an outpost in the back woods. Certainly, it would have been used in some sense a landing spot and the jumping off point, after the portage around the Long Sault Rapids; for it was the nearby Long Sault Rapids which made for much of Dickinson’s Landing history. These rapids, for those of us who remember them, were so swift and so deep and so covered the complete river bed or the north branch from the mainland to Long Sault Island. Impossible for a canoe to navigate, and, even through the center, impossible for a flat-bottom boat to navigate and so travel on the St. Lawrence always had to take into account a whole series of rapids from Montreal west, the most severe of which were the Long Sault Rapids.

Now, to move to the time of the American Revolution, the hated Tories in the United States were the followers of George the 3rd, who remained loyal to him and to the British in their sentiments. They faced so much persecution, that it was much easier for them to come to Canada; and they did in considerable numbers. Forty thousand went to Nova Scotia, another twenty to thirty thousand settled in the area around the Niagara. But several thousand came right here to our particular area, and the grants of land at the uppermost end of the scale were most generous. A major received five thousand acres; a captain three thousand acres; a lieutenant two thousand acres. The noncommissioned officers, (sergeants and corporals) received two hundred, as did a private with fifty extra acres for wife and each child, with each child receiving two hundred acres upon reaching the age of maturity. We all are aware of the planned settlement where the Scottish-Catholics were put closest to the Quebec border to have a common factor of religion with the French speaking Catholics and next the Scottish Presbyterians. Then, the English Presbyterians or Anglicans in Cornwall Township, Osnabruck, and west of us in Williamsburg, were placed the Dutch, and German Presbyterians and Lutherans.

Now, according to the McNiff map of 1783-86, Osnabruck consisted of three concessions and most of the settlers were ex-soldiers of Sir John Johnson’s Royal Regiment of New York or Royal New Yorker’s as they were often called. The roll call from Pringle’s “Lunenburg or the Old Eastern District” shows such large numbers of names which are still familiar to us today. Jacob Countryman, Dr. James Stuart, Jacob Eaman, Henry Hoople, McKenzie Morgan, Michael Cryderman, Daniel Fykes, Philip Empey, Joseph, John Wert, a Dafoe, a Service; and it is amusing to see how some spelling has changed over the years. The Fickes as we know them were Fike, Stata were Steaty, and the Empey’s, Impey; and Wert, Wart. There were a few Scotsmen mixed in there too, for it was at Archibald Macdonnell’s, right near the Long Sault Rapids, that Lady Simcoe and her husband, Sir John Graves Simcoe, Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, stopped for a visit and at the west end was Miles MacDonnell, who, later, was chosen by Lord Selkirk to head his settlement in Red River Valley in Manitoba.

Westbound ship entering Lock 21.

The brow of the high embankment in the background is now just below the surface of Lake St. Lawrence at the western end of McDonald Island in the Long Sault Parkway.

THE LOYALISTS of DICKINSON’S LANDING

Doctor James Stuart (Already discussed under Wales)

James Crowder was a private in the First Battalion of the King’s Royal Regiment of New York. He was in Lieutenant-Colonel John Butler’s Corps of Rangers from 1777 to 1781, and in Captain Alexander McDonnell’s First Battalion in 1783. He was a farmer from Susquehanna River, New York, the son of William Crowder Sr. He settled in Royal Township #3 with his wife, son, and two daughters.

Jacob Eamon was born in America in 1760 and enlisted in the First Battalion of the King’s Royal Regiment of New York on May 22, 1780. He was in Captain John Munro’s Company from 1781 to 1783, and in Captain Archibald McDonell’s Company in 1783. He was a farmer in New York.

Joseph Eamon (No information), Possibly the son of Jacob Eamon above.

James Morden (Mordin) was born in America in 1764, and enlisted in the First Battalion of the King’s Royal Regiment of New York on May 5, 1779. He was in Captain Joseph Anderson’s Company until December 24, 1782, and then Captain Archibald McDonell’s Company in 1783. James Morden was the son of Joseph Morden, from the Mohawk River.

Joseph Fitchet (Fetchet) was born in America in 1765, and enlisted in the First Battalion of the King’s Royal Regiment of New York on May 16, 1780, as a Private. He was in Captain Joseph Anderson’s Company until December 24, 1782, and then Captain Archibald McDonell’s Company in 1783. His occupation was that of a tailor in New York state.

Life in those early days certainly must have been grim. First, there were trees to cut and this meant one of the few cash crops, the sale of ashes, for potash, and barrels of ashes from the maple, elm, the pines and mostly the oak went east to Montreal. If only they had had the foresight to leave a few of those marvellous oaks and maples, and elms rather than all the second growth we have today, but it is understandable that every tree was not a thing of beauty. It was a thing of absolute necessity when one built a home from it, or when burned in your fireplace, but it was only something to be removed when you had to plough around it. The grimness of the life is pointed out by the fact that in 1796, in the Eastern District of Lunenburg, twenty-five pounds was put aside to pay a bounty for the killing of wolves and bears. But by 1811, things had moved to such a point that twenty pounds were granted to bridge the Hoople’s Creek.

The ordinary things of life were continued. According to Elizabeth Hoople’s “Hooples of Hoople Creek”, the first marriage took place shortly before 1786, at the west end of what would have been Dickinson’s Landing, an outdoor marriage under an oak tree in which John Hoople and Eleanor Kentor were joined in marriage.

The small village along the river, probably because it was central, was chosen as the area for the first session of court in the District of Lunenburg, and the court was held here for the first time on the 5th of June, 1789. They continued to be held here for three years. Again, the jury reads like a catalogue or a roll call of local names; Jacob Van Allen, Eamon, Joseph Loucks, John Wert, Jacob Merkle, an Empy, and Nicholas Ault.

There is not too much detail on the cases, however there was one case of assault and battery. A man was found guilty and charged one shilling; so obviously he didn’t batter too much, because in a second case of the day, a man was also found guilty of assault and battery and was fined twenty shillings, so he must have battered a great deal more. In 1790, a man and his wife were tried on charge of petty larceny, and the man was found guilty and the wife was absolved which was just as well because his punishment was to be tied to a post and to given thirty nine lashes on the naked back. In 1791, another prisoner had to stand in the pillory for one hour, but there is no mention of whether or not the townspeople could stand and jeer and spit and carry out the indignities usually associated with this type of punishment.

In the early fifteen or twenty years, obviously the day to day life must have entirely revolved around keeping body and soul together, clearing land, surviving the winter, improving one’s lot, little by little.

The next major event into the lives of the people was the War of 1812 to 1814. Naturally, because we were along the river front, there was some action, the main part of which took place at Crysler’s Farm. But we do know that on the river there was the skirmish at the mouth of Hoople’s Creek, when the American General Brown was coming down river with three thousand men. His arrival in Cornwall was to coincide with the American General Wilkinson, because in Cornwall the government stores were housed, and of course, the American army felt that to take these would weaken the effort on the Canadians. On November 10, 1813, at the mouth of Hoople’s Creek, a skirmish took place. Now mainly, the Glengarry District Militia is mentioned, thirteen hundred strong, but the Second regiment of the Stormont Militia and those from Osnabruck Township, included a Dickinson, an Ault, Morgan, Shaver, Empy, Crysler, Eaman, Dafoe, Nairn and Grant; against so many of the names still with us today.

Now, while the war was coming to an end, an American by the name of Barnabus Dickinson came north from Massachusetts, and, in Montreal, won the contract for the delivery of mail from Montreal and west. It wasn’t until after the war, of course, that he set up his system of public conveyances to carry both mail and passengers with a series of boats and coaches from Montreal. To facilitate part of this, the steamboat Iroquois made a round trip from Prescott to Dickinson’s Landing. But obviously, it wasn’t large enough for the rapids at Farran’s Point and again at Morrisburg, because, in 1834, this steamboat was replaced by one named The Dolphin, which was in service for eight years, but the stretch from Cornwall to Dickinson’s Landing always had to be done by stage coach, again because of the Long Sault Rapids. And by 1832, with this combination of serving as a jumping off spot to the west and an area where goods had to be unloaded from boats, placed in wagons, and taken twelve miles east to Cornwall.

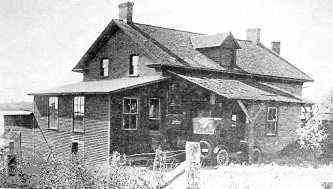

By 1832, Dickinson’s Landing was the second most prosperous village in the whole of the Lunenburg District, a district, incidentally, which ran from east of Brockville to the Quebec border, and north almost as far as the Ottawa River. To show that it was indeed a flourishing area, here is yet another list. It had a gristmill and a sawmill, very importantly; it had a distillery; there was a soap factory which served thepotash industry, still very valuable as far as potash was concerned; there was a tannery, two blacksmith shops; there was a carriage factory and cabinet maker. (Indeed some people in this part of the country, who had very old chairs, thought they were made in a factory in Dickinson’s Landing). There were three shoe shops, two harness shops, two tailor shops, an undertaker, a cooper and tinsmith shop, five general stores and five hotels; one of which was called “Snyder’s Stagecoach Inn”, as well as the St. Lawrence House Hotel, the picture of which I have here, sometimes called the “Bullock House”.

shop, five general stores and five hotels; one of which was called “Snyder’s Stagecoach Inn”, as well as the St. Lawrence House Hotel, the picture of which I have here, sometimes called the “Bullock House”.

Now, in 1834, there was a new development which meant, of course, an enlargement of Dickinson’s Landing, but also sowed deep seeds of the end of Dickinson’s Landing as a place of importance – that was the building of the Cornwall Canal. The sod turning took place in 1834, and the Canal was not opened until 1842, eight years later.

The most difficult stretch in building this canal, which was 11-1/2 miles long, was that from Dickinson’s Landing east to the Long Sault Rapids. The embankment had to be started here, right a Dickinson’s Landing, directly opposite the east end of the village; and such was the rapidity of the current in this area, that it took months  of dumping carts of earth and stone into these fast flowing waters at the head of the rapids, months before a bit of an embankment showed above the surface of the water. The quarries at Mille Roches were used at this time, to supply rock to build the embankment of the Cornwall Canal.

of dumping carts of earth and stone into these fast flowing waters at the head of the rapids, months before a bit of an embankment showed above the surface of the water. The quarries at Mille Roches were used at this time, to supply rock to build the embankment of the Cornwall Canal.

Over a thousand men were employed simply at this end of the operation, and in all towns there seemed to be men, living in tents in the summer and drafty barracks in the winter and being paid minimum wages for twelve to fourteen hour working day. These were rugged men, and as long as they stayed around Dickinson’s Landing, bought their wares at the distillery and kept to themselves; not too much was thought of it; until the murder of the prosperous citizen by the name of Alfred French, he of Maple Grove; the French-Roberston house today is in Upper Canada Village.

To return to the Canal, it was a slope-sided canal, a hundred feet wide at the bottom and a hundred and fifty feet wide at the top, with a series of seven locks from Cornwall to the head of the canal, each one lifting about eight feet or lowering it on its eastern journey, the equivalent eight feet. Lock No. 21 was the last in the series and it was directly east of the church in Dickinson’s Landing; but the canal opened in 1842 and one boat, “The George Frederick” was captained by a man named Sawyer, and was commissioned by two Dickinson’s Landing residents, Adam Loucks and W. Hoople, and it made the run to Cornwall in the astounding time of twenty-five minutes.

Now with the coming of the canal, the loading and unloading process at Dickinson’s Landing was unnecessary, and so, certain of the businesses closed and this decline was further hastened with the opening of the Grand Trunk Railway in 1856. Now the station was a mile north of Dickinson’s Landing and this was called Dickinson’s Landing Station, until, in 1860, the Prince of Wales, later to become King Edward VII, detrained at the Landing station. Legend has it he asked the name of the place and was told Dickinson’s Landing Station and he thought it was rather a long name and asked why it didn’t have a name of its own; so the town fathers decided that it should be named in his honour., So, the village of Wales became a separate identity.

Dickinson’s Landing had lost its boat stops, its stage coach stops, and consequently, it lost many of its businesses. In the 1850’s, there was a big population growth with the coming of the Irish. Two families well remembered in this area were the Clark family and the Murphy’s. Many of the Irish immigrants who came were involved in construction as steam shovel operator, and here they made their headquarters. Their families were born and raised here, but the men themselves were often away at construction and other places. In fact, the Catholic population of Dickinson’s Landing  was sufficiently large that, in 1863, the wooden church, which had served the people, was replaced with a rather handsome building which was called St. Patrick’s, completed that year. Then, an Irish priest served here after and felt that it wasn’t nearly magnificent enough to be called St. Patrick’s because, after all, St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City had been built by that time. He renamed it in honour of our Lady and, hence, Our Lady of Grace came to be. Of course, it is still with us here today in Ingleside, in another form.

was sufficiently large that, in 1863, the wooden church, which had served the people, was replaced with a rather handsome building which was called St. Patrick’s, completed that year. Then, an Irish priest served here after and felt that it wasn’t nearly magnificent enough to be called St. Patrick’s because, after all, St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City had been built by that time. He renamed it in honour of our Lady and, hence, Our Lady of Grace came to be. Of course, it is still with us here today in Ingleside, in another form.

Doctors were always in Dickinson’s Landing, from almost its earliest time; most famous of which was probably Granny Hoople, not in the true sense a medical doctor, but the wife of John Hoople, who as a young girl, had been carried off after her family had been massacred by the Delaware Indians. She lived with them for seven years, and learned all of their herb medicines. People came to her from all over the area for treatment for probably what would today be referred to as ulcers, heart burn and all types of intestinal diseases. It was the same Granny Hoople, who, in 1813, nursed a badly wounded American soldier, who later died. When she talked about it many years later, when she became Granny Hoople, one of the people to whom she told the story, informed the government in Washington of her risk. They rewarded her with a payment of six hundred dollars which, indeed, must have been a very handsome sum in those days. Now, she remained the doctor during the pioneer period, until the arrival of the first medical doctor, Dr. Feader, who came in 1811.

By the 1930’s, Dickinson’s Landing was a quiet village, but it was well lighted for it had street lights at that time with the poles paid for by the Women’s Institute. It had Ransom’s store, as well as the Sweet Briar Cheese Factory, operated by John Snetsinger, the father of Harold Snetsinger. It was a fair sized operation; in the year 1918, it produced one hundred and eighty thousand pounds of cheese and four thousand pounds of whey butter. Dickinson’s Landing, for recreation, had variety.

By the 1930’s, Dickinson’s Landing was a quiet village, but it was well lighted for it had street lights at that time with the poles paid for by the Women’s Institute. It had Ransom’s store, as well as the Sweet Briar Cheese Factory, operated by John Snetsinger, the father of Harold Snetsinger. It was a fair sized operation; in the year 1918, it produced one hundred and eighty thousand pounds of cheese and four thousand pounds of whey butter. Dickinson’s Landing, for recreation, had variety.

At one time, it had three dance halls, and rather well-attended places they were. One of them had an upstairs dance hall in the village. One evening, a fight took place and was considered one of the major fights in this part of the country. I’m sorry that I never made a tape recording one night in my father’s barbershop, when the men were discussing the event. It happened in the 1920s, and there was a lot of action – to the point where it went on for a long enough period of time, that one man left the dance hall, went down to the Long Sault, about a half mile to three quarters of a mile east, and got Captain Anderson. He seemed to have been sort of a giant of a man or a fight settler. He came up to the hall, at which point he began to settle a fight with heaving men out windows. They actually landed down on snowbanks. The men, talking about it years later, and no doubt the story of it was a bit magnified, certainly made it sound like one zinger of a fight.

Races were held in Dickinson’s Landing. There was a race track. This was later bought by rather a renowned horseman in this part of the country, who many of us remembered in Jimmy Conners. Jimmy had a stable, a boarding stable at the racetrack, which was equal distance from Dickinson’s Landing and Wales, right here along the graveyard road across Hoople’s Creek and a little bridge, and up to the beautiful sand track. One horse he had, Gilbert Gratton, wouldn’t race unless an old nanny goat was with him, standing right at the side of the track, wouldn’t go in the horse wagon unless the nanny goat went in first, wouldn’t go into his stall unless the nanny goat was in there, and wouldn’t start a race unless she was standing near the starting line. One time, a new handler of the nanny goat had the goat at the starting line, Gilbert Gratton was off to a good start, but on the second lap, he glanced over and the young lad, with the nanny goat, had left. So Gilbert Gratton just quit. That was the end of the race for him, half way through.

Most of the recreation of Dickinson’s Landing was in the summer time, swimming, boating – many people could simply walk to the edge of the lot and there was the boat in the little wharf, and start the motor and away they’d go. The proximity of the river accounts for so many of the people in Dickinson’s Landing being riverboat men. Frank Dishaw, now retired here in Ingleside, was a riverboat captain; Walter Mills, for many years, was Captain of the Canada Starch Co. ship. Dickinson’s Landing has all sorts of anecdotes; like so many anecdotes, unless one really does know the people involved, the humour is often lost. One thing I’ve always heard was Dickinson’s Landing was a great place for nicknames. The McFees, Alec, who was called Arctic or North, because, of course, he was so frosty, and his brother was called Friday, because he was long and lean. Many people only remembered the village because it was a long skinny village, with a long name, on your way to Montreal, or on your way to Toronto. There wasn’t really very much there to make anyone stop, but it was home to many people until the year of the flood, 1958 A.D.

NAMES OF BUSINESSES

-

H. Snetsinger’s Store

-

J. Connor’s Racing Stables

-

S. Elliott’s Garage

-

J. Warner Tinsmith & Plumber

-

G. Smith’s Turkey Yard

-

S.S. No. 1 Osnabruck Township school

-

Our Lady of Grace Roman Catholic church